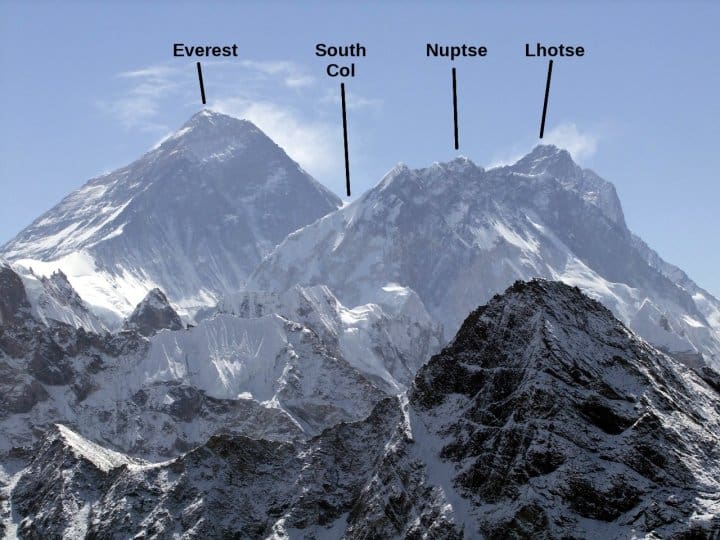

Mount Everest, the world’s highest mountain at 8,848.86 meters (29,031 feet), attracts climbers who want to reach the summit for various reasons. Above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet), they enter what’s known as the Everest Death Zone, where the human body is pushed to its limits.

Swiss doctor Edouard Wyss-Dunant named this zone in 1953, recognising it as a hazardous point. Oxygen levels drop drastically to about one-third of what they are at sea level, yet the body continues to fight. For climbers, being in this zone is a testament to the unbelievable resilience of the human body, with each step testing their physical and mental strength. In this article, you will learn what the Mount Everest death zone feels like on the human body.

What is it Like Being in Everest's Death Zone?

The Everest Death Zone is renowned for its extremely low air pressure. This means there’s much less oxygen available, only about a third of what you’d find at sea level.

Understanding this and being prepared is crucial for climbers.

At sea level, the air is about 21% oxygen, which fills up the haemoglobin in your red blood cells. However, at 8,849 meters, the oxygen level drops significantly.

A significant drop in oxygen level causes hypoxia, when your body doesn’t get enough oxygen. This can harm essential organs, such as your brain and lungs.

Physiological Effects of Low Oxygen

In the Everest Death Zone, the body faces extreme challenges:

- Hypoxia (Low oxygen): When oxygen is scarce, the brain and muscles don’t receive enough, leading to dizziness, confusion, and poor decision-making. This can cause climbers to act irrationally, such as taking off their necessary equipment. According to Wikipedia’s “Hypoxia” entry, low oxygen is a leading cause of failure in the Everest Death Zone.

- Increased Heart Rate: The heart beats rapidly to compensate for the lack of oxygen, often exceeding 140 beats per minute. This puts a strain on the heart, increasing the chance of a heart attack or stroke. This stress is constant in the Death Zone.

- Suppressed Body Functions: The body stops performing essential functions, such as digesting food, to conserve energy, resulting in a loss of appetite. This can lead to rapid weight loss and muscle weakness. Eating becomes almost impossible at these heights.

- Dehydration: Dry air and fast breathing cause climbers to lose fluids quickly, worsening exhaustion and altitude sickness. Dehydration hurts both physical and mental abilities. Climbers must drink water constantly, but it freezes fast in the extreme cold.

Research, such as the work done by physiologist Griffith Pugh in the 1950s, shows that people can’t fully acclimate to altitudes above 8,000 meters. Without extra oxygen, the body starts to fail in 16–20 hours, which could lead to passing out or death.

Extreme Weather and Environmental Hazards

- Freezing Temperatures: Expect average temperatures between -20°C and -30°C. Wind chill can make it feel like -49°C, and exposed skin can get frostbite quickly.

- High Winds: Strong winds worsen the cold and can lead to dehydration, making it risky to move around.

- UV Radiation: The intense sunlight reflecting off the snow can cause snow blindness, a temporary loss of vision.

These factors, combined with the physical demands of climbing, make the Everest Death Zone one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

What Is Rainbow Valley On Mount Everest?

Rainbow Valley on Everest, close to the peak, got its name from the colourful clothing of climbers who died there. It’s a harsh reality check of how risky the mountain is. In the area, you’ll find old equipment, tents, and empty oxygen tanks scattered around, as well as frozen bodies that the cold keeps intact.

The name sounds nice, but it doesn’t reveal the sad truth: it’s a final resting place where climbers, such as Tsewang Paljor (nicknamed Green Boots), have become markers for those climbing the northeast side.

Why Do Bodies Remain in Rainbow Valley

Getting bodies off Everest’s Rainbow Valley is challenging, and here are some reasons.

- Weight and Altitude: A frozen body can be hefty, weighing up to 330 pounds. At 8,000 meters, climbers are too weak to carry heavy loads and can only take about 55 pounds. This makes the transport of bodies nearly impossible.

- Risk to Rescuers: Rescue trips are dangerous. They take long hours of preparation and need a lot of oxygen. In 2024, a cleanup group in Nepal found five bodies. It took days to chip away the ice and cost $20,000 in oxygen for each body.

- Moral Conflict: The decision to leave bodies on Everest is not always a result of the physical challenges of recovery; it is also influenced by broader societal considerations. Some climbers, like Jason Kennison in 2023, desire to remain on the mountain in the event of their death. This sentiment, coupled with the practical difficulties of recovery, can lead to bodies being left on the hill.

Mt Everest Sleeping Beauty: The Story of Francys Arsentiev

The story of Francys Arsentiev, known as Sleeping Beauty on Mt. Everest, is a sad one from the mountain’s dangerous Death Zone. In 1998, Francys and her husband, Sergei Arsentiev, attempted to summit Everest without using supplemental oxygen, a feat achieved by fewer than 200 climbers.

They reached the top, but the way down was a disaster. Francys became exhausted and sick from the altitude, collapsing 800 feet below the summit. Other climbers, including Ian Woodall and Cathy O’Dowd, tried to save her, but before she succumbed to the cold and lack of oxygen, she said, “Don’t leave me.” Her body, frozen in a peaceful position, was nicknamed the Sleeping Beauty of Mt. Everest. It stayed there for nine years until it was moved in 2007.

The Human Cost of Ambition on Mount Everest

The tragic story of Francys and Sergei illustrates the dangers of Everest’s Death Zone. It seems likely that high-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE), which makes the brain swell, played a part in their deaths, causing confusion and, finally, collapse. Their decision to climb without oxygen highlights the risks involved, even for experienced climbers

Notable Fatalities and the Body of Rob Hall

The Everest Death Zone has claimed over 340 lives since the 1920s, with Mount Everest deaths contributing to 1% of all attempts to reach the top. A tragic loss was that of Rob Hall, a well-known New Zealand guide. In 1996, he died during a blizzard that took the lives of eight climbers, including his teammate Scott Fischer.

Rob Hall’s body is still near the South Summit, serving as a reminder of the tragedy written about in Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air. Even Hall’s skill couldn’t protect him from the deadly conditions, showing that even experienced climbers are at risk.

Common Causes of Death on Mount Everest

Deaths on Everest are mainly due to these reasons, based on studies and records:

Altitude sickness: Many deaths are caused by acute mountain sickness (AMS), HAPE, and HACE. A study in The Lancet 2008 mentioned that HACE can impair cognitive function.

Exhaustion: Extreme physical depletion in the Everest Death Zone can cause mistakes. The 1996 disaster is an example of this.

Environmental dangers: Significant factors include Avalanches, falls, and exposure to extreme cold or strong winds. In 2014, an avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall claimed the lives of 16 Sherpas.

The 1996 Disaster: A Case Study

The 1996 Everest tragedy remains the deadliest single occurrence, with 12 people dying. Overcrowding, late descents, and a sudden storm stuck climbers in the Everest Death Zone. Rob Hall’s group, made up of clients and guides, met conditions that could not be survived, pointing to how erratic the zone can be.

Is Kilimanjaro less dangerous than Everest?

Climbing Kilimanjaro requires a level of preparation, but in many ways, it’s less dangerous and much safer than Everest. A table has been drawn below to highlight the factors differentiating the challenges of climbing the two mountains.

Aspect | Mount Everest | Mount Kilimanjaro |

Altitude | 8,848.86 meters (29,031 feet) | 5,895 meters (19,341 feet) |

Death Zone | Above 8,000 meters | None |

Oxygen Levels | ~33% of the sea level at the summit | ~50% of the sea level at the summit |

Death Rate | ~1% of summit attempts | <0.1% of summit attempts |

Climbing Duration | 6–8 weeks for acclimatisation | 5–9 days |

Main Risks | Hypoxia, HACE, HAPE, frostbite, avalanches | AMS, hypothermia, falls |

This table highlights why Kilimanjaro is a more accessible adventure, offering a safer option for many travellers. In contrast, deaths on Mount Kilimanjaro are rare, with a casualty rate of less than 0.1%, making it a safer option than Everest’s treacherous heights.

Why the Death Zone Fascinates Adventurers

The Everest Death Zone is captivating because it pushes people to their limits. The stories, such as those of Francys Arsentiev and Rob Hall’s body, inspire respect and caution. For adventurers wanting a safer yet thrilling option, Mount Kilimanjaro is an alternative. Its cultural value and lower risks make it a good start for those who hope to one day climb Everest.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Can supplemental oxygen guarantee safety in the Death Zone?

Supplemental oxygen helps climbers combat hypoxia in the Everest Death Zone, but it’s not foolproof. Equipment failures, limited tank supply, or extreme conditions can still lead to fatal outcomes. Proper preparation and timing remain crucial.

2. Why do climbers die in the Death Zone?

Climbers die on Everest due to low oxygen, extreme cold, exhaustion, and environmental hazards like avalanches. High-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) and pulmonary oedema (HAPE) are common culprits.

3. How long can someone survive in the Death Zone?

Without supplemental oxygen, survival is limited to 16–20 hours. With oxygen, climbers like Pemba Gyalje have endured up to 90 hours, though this is exceptional.

4. How do climbers prepare mentally for the Everest Death Zone?

The Everest Death Zone demands mental resilience due to extreme stress and fear. Climbers train through visualisation, stress management, and team-building exercises. Mental preparation helps them stay focused despite the zone’s life-threatening challenges.